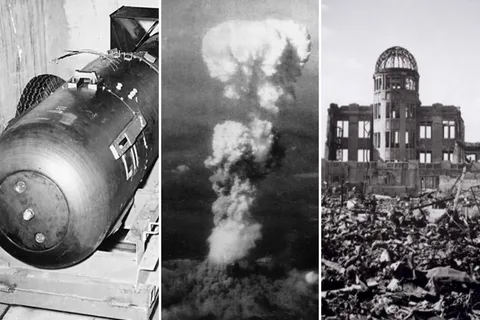

In the history of human fighting, few occasions have had as significant an effect as the dropping of the nuclear bomb. On August 6, 1945, the world saw a vacant kind of pulverization, one that was profound for a long time. The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan were bombed by two bombs—”Little Boy” and “Fat Man”—ushering in the minuscule age.

The bombings, which slaughtered over 200,000 individuals right away and in the days after, cleared out a stamp on worldwide awareness that proceeds to reverberate today.

But how did we reach this point? And more vitally, what were the results of utilizing such a capable weapon?

What technology was used to make the atomic bomb?

The nuclear bomb wasn’t made overnight. It was the result of a long time of logical investigation, political choices, and military techniques. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the world was overwhelmed by World War II, and it was clear that whoever had the most advanced innovation would likely win. Germany had now begun investigating atomic fission—the handle that seems to discharge an enormous sum of vitality by parting a molecule. In reaction, the Joined Together States started the Manhattan Venture, a mystery program pointed at building a nuclear bomb sometime before the Nazis could.

Physicists like Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi were key players in persuading President Franklin D. Roosevelt to contribute to atomic inquiry. By 1945, beneath the authority of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the U.S. had effectively tried to begin with the nuclear bomb in the deserts of unused Mexico. This was known as the “Trinity Test.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Exceptional Days

After Germany’s yield in May 1945, the war proceeded in the Pacific, where Japan showed no signs of backing down. The U.S. government, under President Harry S. Truman, accepted that dropping the nuclear bomb would constrain Japan to yield without assisting expensive battles.

Three days afterward, on August 9, the U.S. dropped “Fat Man” on Nagasaki, slaughtering another 70,000 individuals. This moment of bombarding was sufficient to thrust Japan to yield, finishing World War II.

But the human toll didn’t halt with the war. Radiation harming, burns, and wounds driven to long-term well-being impacts. Survivors, known as hibakusha, managed the physical and mental scars of the bombings for the rest of their lives. In expansion, future eras in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were born with hereditary transformations and other well-being issues due to radiation exposure.

The Ethical Wrangle: Was It Justified?

The atheist bomb one of the most imperative and questionable questions encompassing the nuclear bombings is whether they were legitimized. Supporters contend that the bombs spared lives by bringing a quick conclusion to World War II. They claim that without the bombings, the U.S. would have had to attack Japan. Which may have driven millions of people to pass on both sides. In truth, military pioneers evaluated that an attack might taken a toll on the U.S. over a million lives.

However, pundits contend that Japan is, as of now, on the brink of yield and that the utilization of nuclear weapons is pointless. A few see the bombings as a war wrongdoing. Particularly given the gigantic civilian casualties. Besides, others point out that the bombings set a perilous point of reference for future conflicts.

It’s difficult to reply whether dropping the bomb was right or off-base. It was a choice made in the warmth of war, with colossal weight and inadequate data. What is clear, though, is that the nuclear bomb changed the way the world sees warfare.

At the beginning of the Atomic Age the atomic bomb

The consequence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki stamped the start of the atomic age. Nations around the world rapidly realized the control of nuclear weapons, and a worldwide arms race started. The Cold War between the Joined together States and the Soviet Union was generally characterized by the fear of atomic war. For decades, both nations stockpiled thousands of atomic warheads, making an unsafe standoff known as “commonly guaranteed devastation” (MAD).

In a way, the nuclear bomb has to be both a weapon of war and a device of discretion. Whereas no atomic bombs have been utilized in the struggle since Nagasaki. The unimportant presence of these weapons has formed worldwide legislative issues. Atomic deterrence—the thought that nations are less likely to go to war if they fear atomic retaliation—became a central column of worldwide strategy.

The Human Side of the Nuclear Bomb

While it’s simple to get misplaced in the legislative issues and military methodologies encompassing the bomb, it’s imperative to keep in mind that humans take a toll. Behind each measurement is a life, a family, and a story. Survivors of the bombings have gone through decades sharing their encounters to guarantee that the world never overlooks the repulsions of atomic warfare.

“I saw my family vanish in front of my eyes,” reviewed one hibakusha. Who was a fair child when Hiroshima was bombarded? Stories like these make it clear that atomic weapons are not fair and disobedient of destruction—they tear separated lives in incredible ways.

A Future Without Atomic Weapons?

In later times, there has been a developing trend toward atomic demilitarization. The Atomic Non-Proliferation Settlement (NPT) points to decreasing the number of atomic weapons in the world and avoiding their spread. A few nations have made strides in diminishing their stockpiles. But the risk of atomic war remains. Countries like North Korea proceed to create atomic programs, and pressures between nuclear-armed states persist.

The nuclear bomb is an update of the dangerous control that people can use. But it too serves as a lesson in the significance of discretion, participation, and peace. In conclusion, we must ask ourselves: Can the world manage another Hiroshima?

While the bomb may have finished one war. It moreover began an unused kind of fear—one that still frequents us nowadays. The nuclear bomb is not a fair history; it’s a challenge to our future.